This is a review of the paper Managing the development of large systems by Winston W. Royce, originally published in August 1970.

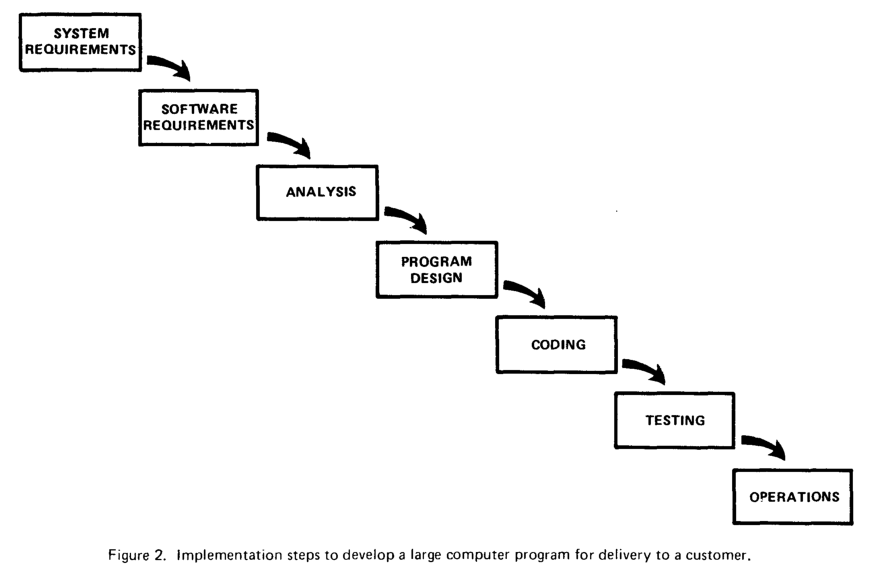

Figure 2 of this paper often cited as the "waterfall" method, a model that considers the project's activities as a linear sequence of steps. In fact, this figure is only the starting point of the paper. Royce acknowledges that the depicted model doesn't work in practice and he suggests five concrete steps that are required for large software projects to succeed.

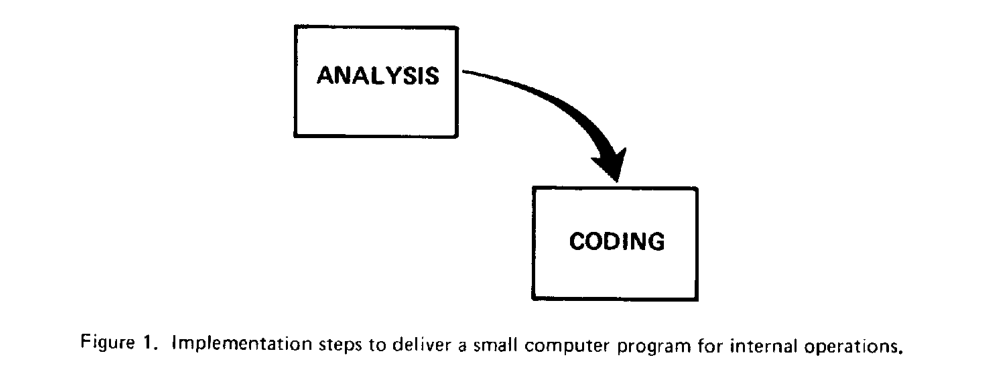

Analysis and coding

The paper starts with the observation that there are two essential steps common to all computer program development: analysis and coding.

The author doesn't discuss these steps in detail. I understand the first step as analysis of the problem at hand and the second as the activity spent typing in the code, debugging, and deploying. In other words, first we define what the desired program is indented to do, then we implement it.

Royce claims that this simple, two-step development model works for systems where the final product is operated by the those who built it. The rest of the paper extends this model to explain the development of larger systems:

"[...] to manufacture larger software systems [...] additional development steps are required, none contribute as directly to the final product as analysis and coding, and all drive up the development costs."

We will see later that by additional development steps the author means program design, defining requirements, writing documentation and testing. It seems that in already in 1970 many people didn't understand that a software project is much more than just coding:

"Customer personnel typically would rather not pay for them [the additional steps], and development personnel would rather not implement them. The prime function of management is to sell these concepts to both groups."

Nevertheless, Royce holds the management responsible to explain the structure of the project and the purpose of each step in it.

The author managed the "development of software packages for spacecraft mission planning, commanding and post-flight analysis". Drawn from the author's experience, the paper proposes a development model that is required, but not sufficient, for such software project to succeed.

In the sixties the most expensive and most complex software projects solved scientific and engineering problems, often using hardware with constrained resources. Royce clearly makes his claims in this specific context, so perhaps it's foolish to extrapolate to the development of any software project.

Not waterfall

The third paragraph introduces the "additional steps" the author hinted in the introduction:

"A more grandiose approach to software development is illustrated in Figure 2. The analysis and coding steps are still in the picture, but they are preceded by two levels of requirements analysis, are separated by a program design step, and followed by a testing step."

Looking from the manager's perspective, Royce continues:

"These additions are treated separately from analysis and coding because they are distinctly different in the way they are executed. They must be planned and staffed differently for best utilization of program resources."

The nature of the work in these steps is different, so it makes sense to think about them separately. Royce doesn't specify how these steps are executed. In fact, he doesn't discuss this figure any further because this is just an intermediate step, and he's not finished presenting his model yet.

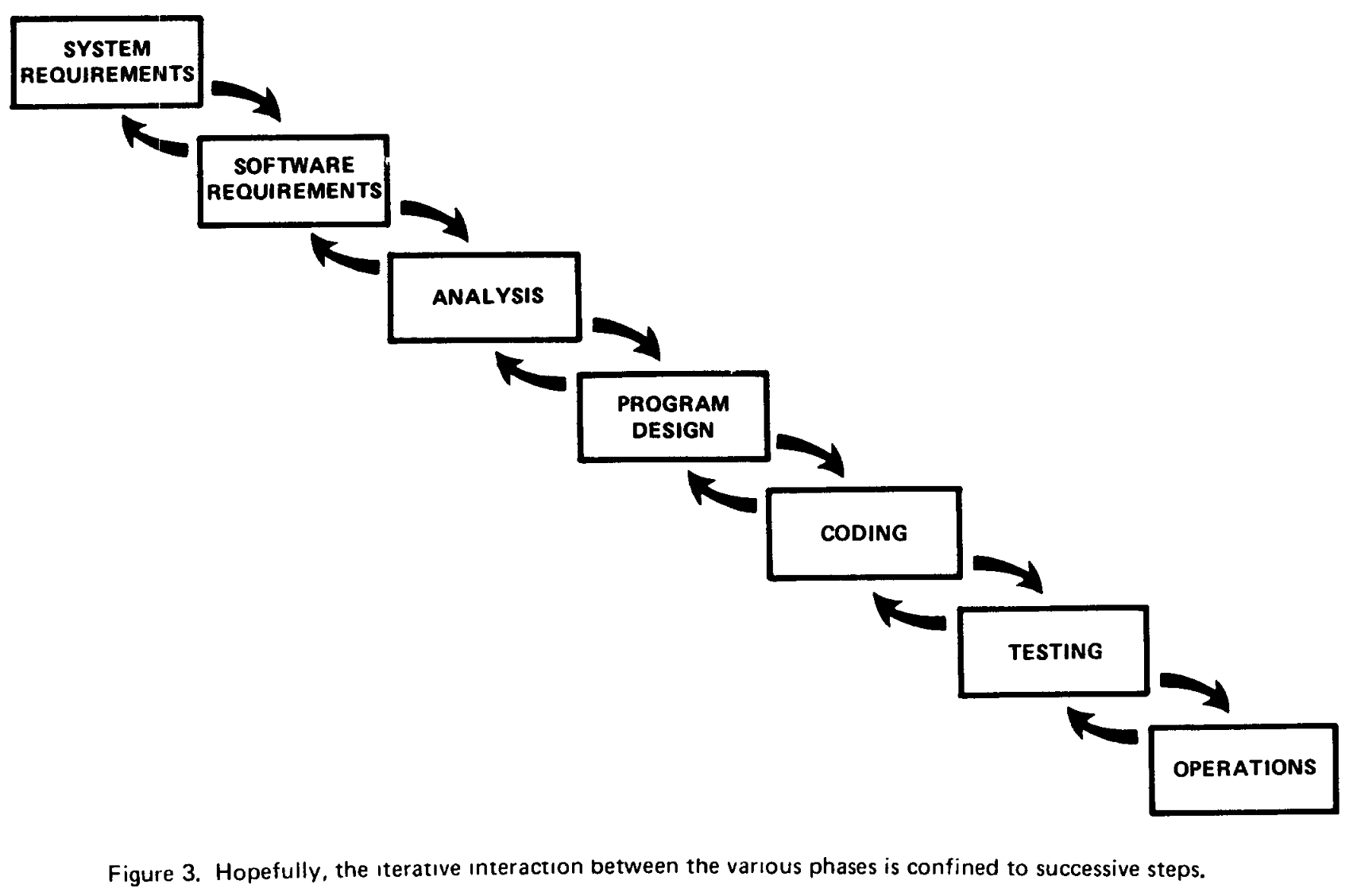

Local iterations are insufficient

In Figure 3, Royce shows an iterative relationship between successive development steps.

Royce believes in this approach. He thinks these small, local iterations have value because:

"[...] as each step progresses and the design is further detailed [...] The virtue of all of this is that as the design proceeds the change process is scoped down to manageable limits."

Adapting the design in small chunks has benefits, but he immediately points out that following this process is "risky and invites failure". The problem is that iterations only occur between preceding and succeeding steps but rarely in more remote steps in the sequence. Royce gives an example:

"The testing phase which occurs at the end of the development cycle is the first event for which timing, storage, input/output transfers, etc., are experienced as distinguished from analyzed. [...] if these phenomena fail to satisfy the various external constraints, then invariably a major redesign is required."

With local iterations only, fundamental design problems surface too late in the project. In effect, the development costs increase and the project runs late.

Before discussing the mitigations, Royce closes this section with a note on the role of coding:

"One might note that there has been a skipping-over of the analysis and code phases. One cannot, of course, produce software without these steps, but generally these phases are managed with relative ease and have little impact on requirements, design, and testing."

It is not the implementation, but discovering the requirements, finding a solid design and defining a test plan are the risky parts of the process.

Eliminate development risks

In the main part of the paper Royce presents five steps that, in his experience, increase the likelihood of success. These are:

- Program design comes first

- Document the design

- Do it twice

- Plan, control and monitor testing

- Involve the customer

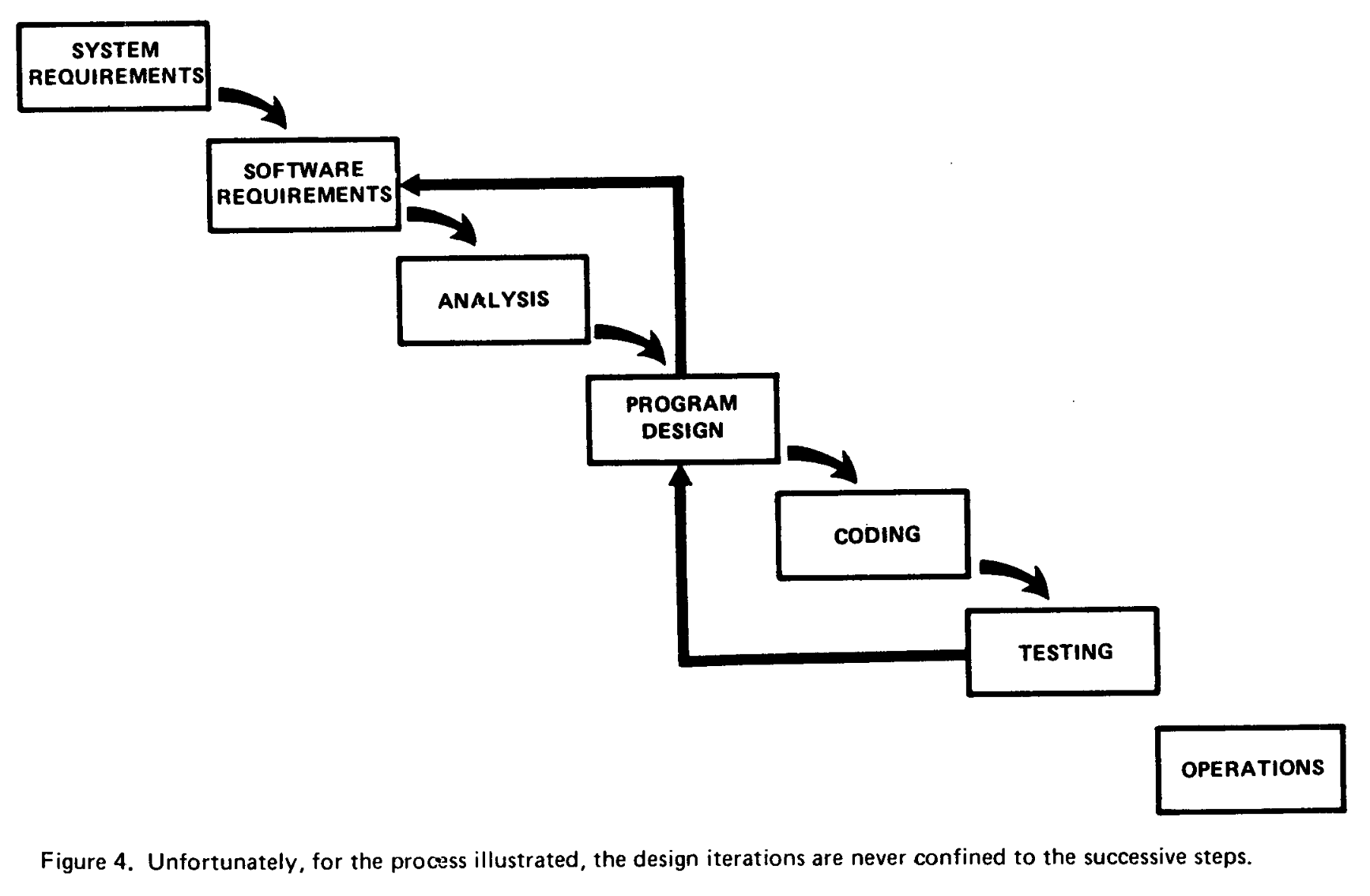

The process is shown in Figure 4, let's see each steps in detail.

Program design comes first

In center of Figure 4 is "Program design", this is where the process starts. Program designers lay out the operational design of the program, they design, define and allocate data processing modes even at the risk of being wrong.

Eventually, all software is about data transformation therefore understanding the data is key to understanding the problem. The recommendation here is detailed and prescriptive:

"Allocate processing, functions, design the database, define database processing, allocate execution time, define interfaces and processing modes with the operating system, describe input and output processing, and define preliminary operating procedures."

The outcome of this phase is an overview document with a goal that:

"Each and every worker must have an elemental understanding of the system. At least one person must have a deep understanding of the system which comes partially from having had to write an overview document."

Interestingly, in his 1980 Turing-award lecture, Tony Hoare recounts a story of a cancelled project from the sixties where he felt responsible for the failure because he let the programmers do things which himself didn't understand.

Document the design

Royce starts the longest section of the paper with a categorical statement:

"The first rule of managing software development is ruthless enforcement of documentation requirements. [...] Management of software is simply impossible without a high degree of documentation."

A verbal record is intangible to be a basis for a communication interface or management decision. Without a written record one cannot evaluate the project's progress nor its completion.

Documentation serves as the primary means of communication between people on different parts of the project: developers, testers, people in operations. Additionally, good documentation permits effective redesign, updating and retrofitting without throwing away the entire existing framework of operating software.

How much documentation is enough? According to Royce, in 5 million dollar (approximately 38 million in 2023) software project, an adequate specification document would be around 1500 pages long.

Do it twice

If the product is totally original, Royce recommends building a prototype which he calls an early simulation of the final product:

"If the computer program in question is being developed for the first time, arrange matters so that the version finally delivered to the customer for operational deployment is actually the second version insofar as critical design/operations areas are concerned."

The goal of the prototype is to test which hypotheses hold and identify areas of the design which are too optimistic. Royce highlights that the personnel involved in the pilot must have an intuitive feel for analysis, coding and program design. In other words, the most experienced engineers in the team should be assigned to this work.

Plan, control and monitor testing

This part on testing is the second-longest section of the paper, here I highlight only a few points.

If the project followed the previous steps, most problems should be already solved:

"The previous three recommendations to design the program before beginning analysis and coding, to document it completely, and to build a pilot model are all aimed at uncovering and solving problems before entering the test phase."

In this section Royce observes that most errors are obvious, and he argues for performing code reviews: every bit of code should be subjected to a simple visual scan by a second party who did not do the original analysis or code.

He also promotes good test coverage: every logic path in the computer program at least once with some kind of numerical check. He puts the bar high: as a customer he would insist on nearly 100% coverage.

Involve the customer

Royce recognizes that even after an agreement, what the desired software is going to do is a subject of wide interpretation. He suggests that the customer is formally involved during design reviews and during the final software acceptance review.

Discussion

I am surprised how many ideas, that we consider as "modern", are present in this paper from 1970. Designing data flows, pilot projects, code reviews, customer involvement are all mentioned here by someone who managed projects during the sixties. Computing was totally different then, but software projects suffered the same problem as today.

More than fifty years later, I feel that the Royce's wisdom remains relevant. Many suggestions in this paper were rediscovered or reformulated later, perhaps some are still ignored.

This is a fantastic paper. The original is only 11 pages, I highly recommend reading it.

Acknowledgements

The figures in this article are from the original paper.